Jonathan Glatt: The Lightbulb Moment

October 1, 2013

Every designer has had that moment in their life, that work of art, that conversation, that experience, when the light bulb goes off and the very idea of what great design is, and means, comes into focus. In college, I was lucky to have an internship in the American Furniture Department at Sotheby’s under Leslie Keno and John Nye. The office was piled high with reference books and past sale catalogs, which I poured over during every free minute I had. The pages were filled with examples of furniture from America’s colonial past up through the 1840s. Page after page of similar forms, all slightly different because they were all hand crafted in small workshops, making each piece subject to the maker’s, or client’s, immediate whim. There were highly carved case pieces from Philadelphia, heavily sculpted forms from New York, Folksy pieces from Connecticut, and then there was a highboy from my adopted state of Rhode Island.

At first, the only reason I lingered over this highboy was because it was given top billing and a price fifty times higher than pieces that I deemed similar, or maybe even better.

I could not stop ruminating on this piece, what wasn’t I seeing? It did not have elegant carving, no showy wood grain, simple hardware. What was I missing? There was a Philadelphia Highboy, 1758, estimate $30,000-50,000; a Boston Highboy, $80,000-120,000; both with beautiful carving, gilt details and stunning wood. Then there was this sober looking Newport Highboy, ca. 1760, $300,000-500,000!

The highboy was made by the Goddard-Townsend family of cabinet makers, renowned for their invention of several uniquely American furniture forms, from dense mahogany, right off the merchant ships in Newport Harbor.

At first the sight of the piece, induced a mental shrug where I said, “big deal, I don’t get it, it’s so plain.” At the same time I knew there was more and as I looked, and looked… and looked. It dawned on me that the detail was not missing, it was integrated into every surface and proportion. I had been looking at quality in terms of the icing only, this was an amazing cake, with icing that complimented and enhanced the effect. This was wrought by a confident master. Everything added, there were no extra flourishes, it was refined, but not in the modernist way.

Today we often hear designers talk about stripping back to a minimal form. I think the confusion lies in the difference between minimal and minimum form. Minimum form hedges towards engineering and purely structural needs. Minimal form, allows for aesthetics to drive design, making engineering the servant not the master. Minimal also allows for detail and embellishment when it serves and enhances an underlying form that has integrity. And that was what I was missing, when I first saw this piece, it has irreproachable design integrity. This piece taught me to be basic and to refine without being coldly minimal. It was, and is, honest and beautiful design that transcends style. It was also the piece responsible for me becoming a furniture designer and for pushing me, or possibly cursing me, to never be satisfied with anything other than the “real” thing.

Thanks for reading, I would love to hear about the moments that shaped your design outlook.*

For a modern New England Highboy see:

http://richard-watson.com/furniture.php

*Since then several Goddard-Townshend pieces have sold in 2-3.5 million dollar range.

-Jonathan Glatt

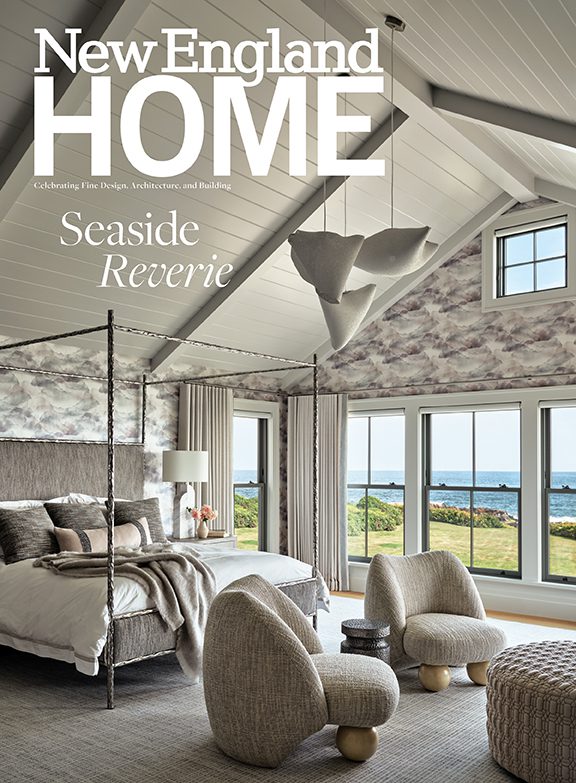

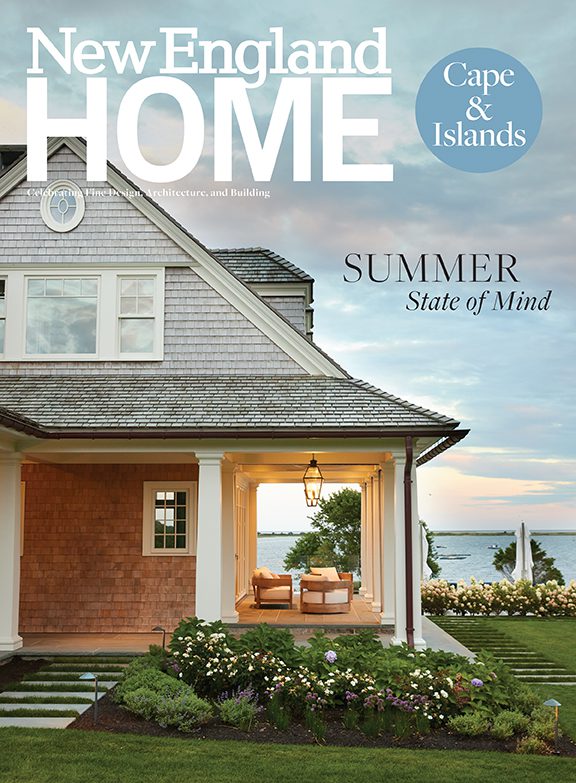

Jonathan Glatt is the “G” in O&G Studio in Warren, RI a furniture company known for their New England Modern style. Jonathan and his business partner, Sara Ossana, were recently awarded NE Home’s 5 under 40 Award. In addition to O&G, Jonathan teaches 3-D design at Bridgewater State College.

Share

![NEH-Logo_Black[1] NEH-Logo_Black[1]](https://b2915716.smushcdn.com/2915716/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/NEH-Logo_Black1-300x162.jpg?lossy=1&strip=1&webp=1)