Coastal Building

June 30, 2017

The special nature of the Cape and islands—from the weather to the fragile ecosystem—means designing and building homes requires extra creativity, tenacity, and resourcefulness.

Text by Paula M. Bodah

The whiff of seawater in the constant breezes, the play of light on dunes and scrub, the quick-change artistry of the weather on any given day—these are a few of the things that make Cape Cod, Martha’s Vineyard, and Nantucket so special to those who live there. For the people who work in the residential design business in the area, those elements also pose special difficulties. How does an architect design a house that makes the most of a waterfront site but doesn’t damage fragile sand dunes? How does a contractor build a house that can stand up to wind-driven rain? What will that fabric that seems perfect in the light of the Boston Design Center look like in the unique light of a Cape or islands home? What plants will survive salt spray and frigid winds and look beautiful come summer?

It’s all in a day’s work for the area’s architects, designers, builders, and landscape architects. Where some might see challenge, they see opportunity. “I think it’s more exciting,” says Barnstable-based architect Doreve Nicholaeff. “Restrictions, limitations, make you think more creatively.”

Here’s what our region’s design professionals had to say about the subject.

Architecture and Building

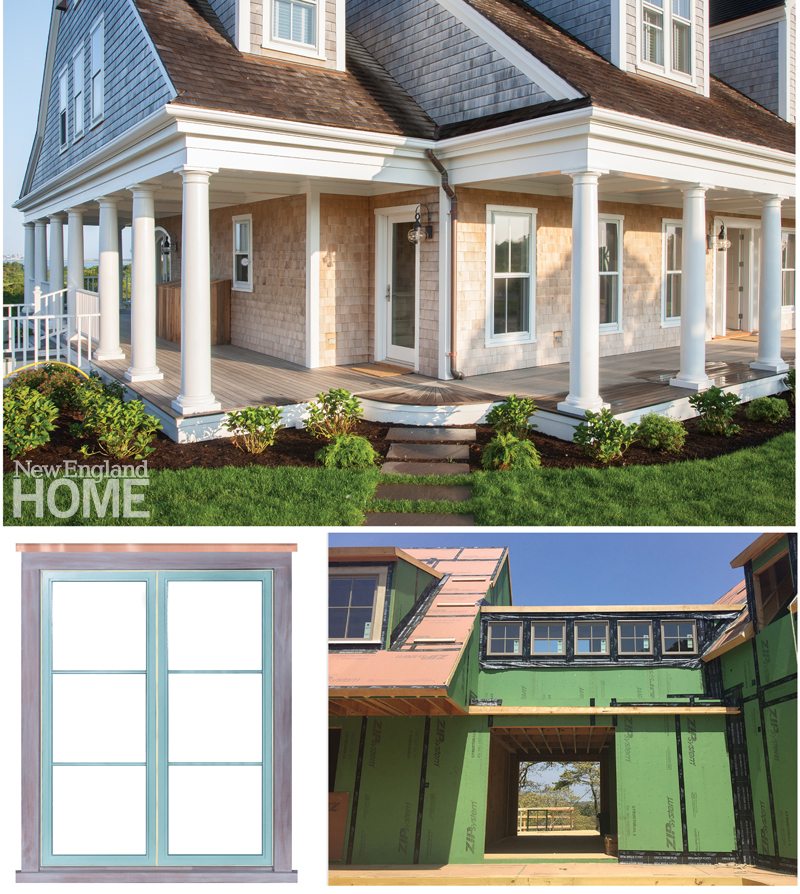

The idea of a Cape Cod home inspires thoughts of sweet cottages with weathered shingles and white trim. The classic style has its many fans, to be sure, but today’s Cape and island homes run the gamut from traditional to modern. Vineyard Haven architect Peter Breese says his firm is working on two Martha’s Vineyard homes that couldn’t be more different. “The one on the west side of the island is very contemporary,” he says, “and the one on the east side is absolutely precious—it looks like a turn-of-the-twentieth-century structure.”

Every project is different, says Nicholaeff, because no two sites are the same. Designing a house on the Cape’s north side means working to get as much light into the structure as possible, while on the south side of the island, the design might mean mitigating strong afternoon light. “We designed a north-oriented house to be just one room deep and used clerestory windows, so the sun goes through the house all day,” she says.

Conservation regulations and codes related to protection from wind and water have an impact on design, as well. To replace an old house with a new one on a lot that sits close to a Sandwich salt marsh, Yarmouth Port architect Joseph W. Dick kept the original footprint but lifted the house and set it on pilings. By law he could have built a larger house. “So many houses in this area get torn down and the people get permission to build much larger houses closer to the dunes,” he says. In his view, protecting those precious dunes was a crucial part of the project.

Flood zone, velocity zone (meaning the possibility for damage from strong waves), and hurricane code regulations all have an impact on the design of a house and the materials used. Builder Matthew H. Cole, of Cape Associates, says, “Building in a coastal area, like we have for forty-six years, the methods get tested quickly and vigorously by the weather.” Peel-and-stick membranes that go under roofs and cladding help protect against wind-driven rain, for example. Spray foam insulation creates a better barrier against moisture and windblown snow than the old pink fiberglass insulation. And when it comes to siding, while people often want vertical or horizontal boards for a more contemporary look, Cole says, “You’d have a hard time convincing me there’s a more effective material than cedar shingles.”

Ipe wood decking and cedar window cladding are materials favored by builder John Kruse of Sea-Dar Construction in Boston and Osterville. Still, warns Tony Shepley, of Shepley Wood Products, there’s no such thing as maintenance-free materials. “Maintenance-free is a fallacy,” he says. “Everything requires some upkeep.” If you want to know what works, however, a Cape or islands builder is the person to ask. “When you figure out how to make it work on Cape Cod, it’s going to work anywhere,” Shepley says.

Another consideration for building in flood zones, Kruse notes, is where to put pipes and wires for plumbing and electricity. “We have more houses that are elevated, on stilts,” he says. “In a normal house you can put mechanical stuff in the basement, but now you have to have all that stuff up above the water line.”

Alex Higgins, senior project manager at Nicholaeff Architecture + Design, says that deep roof overhangs can pose a challenge. “A big overhang is like a wing,” he says, “so we use special fasteners and hold-downs to keep the roof from lifting.”

Nantucket architect Chip Webster prefers to stay away from overhangs altogether. While it may seem that a deep overhang would protect the house from rain, Webster finds the wind often sends the rain sideways, so it blows up under an overhang and can cause problems. One of his projects looks like a classic, complete with cedar shingles, dormers, and a widow’s walk, yet, he says, “There’s almost zero roof overhang. The eaves extend just enough to finish the molding.”

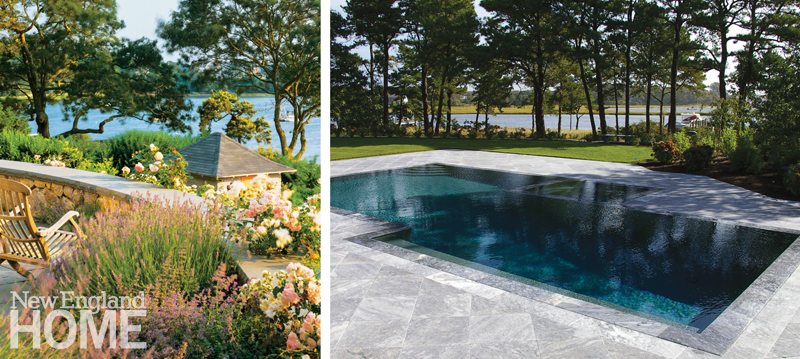

Of course, as harsh as the weather can be in the winter, Webster says the beautiful summers figure into his design, too. People want to make the most of fine weather, but the area is known for an almost constant southwest breeze. For a Falmouth home, Webster set the pool in the L formed by the wings of the house to protect it from the wind.

Interior Design

Designers and builders alike say that one huge factor, especially on the islands, is trying to keep to a schedule that can so easily be disrupted by weather. What’s more, many clients are determined to have their house built or remodeled and decorated before Memorial Day so they can enjoy the summer. “I need a plan A, B, and C,” says Nantucket designer Donna Elle.

There’s no one “Cape and islands” design style, “But there’s always a seaside vibe,” Elle says. How that vibe comes across depends in large part on finishes. For clients who had a sophisticated, understated style but loved the old Nantucket feel of the cottage that was torn down to make way for their new house, Elle devised a dining room with shiplap walls, then added a sculptural table of dark wood surrounded with clear acrylic Ghost chairs.

It’s all about the environment, says Irina MacPhee of Pastiche of Cape Cod, in Barnstable. The house can be elegant or casual, traditional or contemporary, but it should in some way reflect its environment. On the Cape, she says, “I’m not going to put velvet on a sofa. I’m not going to have a highly polished mahogany side table. We’re not doing tassels or jabots for window treatments.” Instead, one of the new indoor-outdoor fabrics that are durable and beautiful might cover the sofa. The side table may be finished with a weathered-looking paint. And the draperies might be sheer, with a French pleat for elegance, so they billow in the breeze through an open window.

Nantucket designer Kathleen Hay is always mindful that her clients are drawn to their homes primarily because of the water. “The interiors need to be quiet, rather than compete with the outside,” she says. She usually uses a driftwood or subtle pickled finish on white oak floors for a quietly casual look and to disguise the sand that inevitably gets tracked in.

Hay likes shutters as a window treatment alternative. They’re simple and clean, and they stand up to the bright light, she says. The quality of the island’s light figures into her palette and materials, too. “Nantucket light does not forgive,” she says. “A fabric with a little sheen in the showroom will glare in the island light.”

“Living and working in a coastal environment offers so much inspiration,” says Liz Stiving-Nichols of Martha’s Vineyard Interior Design. Most of the homes she designs are vacation homes, which, she happily notes, means her clients are up for a bit of fun. Coastal-inspired colors and materials—lots of blues, whites, and sand hues—as well as accessories with a subtle nautical touch are common, but every home has its unique look and feel, based on the clients’ personality and style. Like the other designers, Stiving-Nichols is enthusiastic about the latest generation of indoor-outdoor fabrics. Crypton, Holly Hunt, Schumacher, Lee Jofa, Perennials, and Kravet, among other companies, offer a wide range of colors, patterns, and textures that have a soft hand and luxurious look, but wear like iron, they all say.

Landscape Design

A house isn’t complete without a beautiful landscape plan. It’s not just about gardens, however. Architects, designers, and landscape professionals agree that the outdoors should be considered an integral part of the house—another room, really—especially when it holds a swimming pool. “The pool is an important part of the schematic,” says architect Breese, “particularly on smaller lots. We consider the pool the same way we do any structure on the property.”

John Viola of Viola Associates in Hyannis says pools, spas, and waterfall features are growing in popularity among Cape and islands homeowners. “Most people on the water want an infinity edge pool,” he says. Beautiful as they are, infinity edge pools require meticulous planning and engineering. “You have to be careful about the amount of water you’re pushing out of the pool and into the trough below,” Viola cautions. On most jobs, he works closely with the architect and landscape architect, and conservation and ground water regulations add complexity to the project. It’s worth it, though, he says. “The sound of water moving and the visual of water spilling are so soothing.”

Falmouth-based landscape architect Kris -Horiuchi, of Horiuchi Solien, says that the same qualities that make landscapes by the shore so special also pose challenges. The sand we love to walk barefoot in permeates the soil. “We either need to amend soils so they retain more moisture, or select plants that can thrive in drought conditions,” she says. “These can be native woody species, meadow grasses, and wildflowers, or ornamental plants. Often, we will integrate a mix of plants that ‘play well in the sandbox,’ such as lavender, Russian sage, bearberry, and beach roses.”

That ubiquitous wind and salty air can scorch plants, too, she says. To help plantings cope, she starts with small plants that can acclimate to a site’s conditions over time, and sets them in groups so they can shelter each other.

Hardscaping choices often include limestone and granite, which are cooler underfoot than bluestone. Hardy cedar, mahogany, and ipe are her preferred deck and fencing materials, while copper, bronze, and stainless steel for fixtures, hardware, and outdoor showers hold up to the salty air better than other metals.

As for those pesky regulations, “we take them in stride,” Horiuchi says. On a recent project, the vegetation was so thick and tall, the ocean was barely visible. When she realized it was made up of invasive and non-native plants, she devised a plan to replace them with new native grasses, shrubs, and trees. “The Conservation Commission approved the proposal because the resulting coastal buffer would be naturalized and enhance the wildlife habitat. At the same time, our client enjoyed a significantly greater water view.”

This article originally appeared in the 2017 issue of New England Home Cape & Islands with the headline Beyond Beauty.

Share

![NEH-Logo_Black[1] NEH-Logo_Black[1]](https://b2915716.smushcdn.com/2915716/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/NEH-Logo_Black1-300x162.jpg?lossy=1&strip=1&webp=1)

You must be logged in to post a comment.