Believe It or Not

May 28, 2010

Text by Louis Postel Photography by Michael Fein

“Run, it’s the Client from Hell,” says the meticulous young draughtsman to the office assistant. The Client from Hell breezes by them to corner a bow-tied gent we shall call Edmund S., the firm’s principle. E.S., as he’s known on Cape Cod and in Westport, Connecticut, wears a goatee with a purposeful Mephistophelean air. “Everything must go!” the client says. “It’s just awful. I need you to get rid of it.” E.S. raises an eyebrow, more amused than angry. It’s not for nothing that he’s earned a reputation for being able to deal with clients every other architect has “fired.” At stake are thousands of tons of marble, thousands of hours of highly skilled labor. The assistant and the draughtsman listen as architect and client confer by the window. After a while, they hear E.S. say to the Client from Hell, “Oh, my dear, you are so-oooh crazy!” more as sly compliment than criticism.

It’s hardly news that client relations represent the single most important factor to design success. Who comes back a second time makes all the difference, especially in difficult times. What is news is that you don’t necessarily have to be a gentle soul with a Mephistophelean goatee to make those relations work. You just need an understanding of what makes people tick. Psychologist Richard Schwartz at the Center for Self-Leadership in Chicago laid the foundation of this structure twenty years ago. Since then, his model has taken off, especially in New England for some reason. The old psychology would ask the designer to figure out what the client wants and ignore his or her nuttiness. In contrast, Schwartz suggests those nutty parts should be heard and respected. Maybe your client believes an Italianate roof welded to your Shingle Style design “has got to be!” There is a reason for this view: the client has a belief, probably from childhood, that this particular design makes a home a sanctuary. That shag rug has to be in the corner because another client has some deep-seated belief that this is what coziness looks like. The stronger the emotion, the more you know it’s a belief expressing its often primitive interpretation of “home as sanctuary.” So play nice with these beliefs.

Boston architect John Battle notes that people often seem to believe a high-tech home has to be modernist in style. “My practice is more rooted in a traditional vocabulary, but technically it’s state of the art,” he says. He’s working on a house on Lake Champlain in Vermont that’s powered by tracking solar panels, a geothermal heat pump and an industrial-strength wind turbine that will generate enough juice to sell the excess back to the state. “The owner went around to the abutters and said he was thinking of putting up a windmill for himself,” Battle says. “They all said ‘Hey, that’s a pretty interesting idea!’ ” Up went a big turbine, and the neighbors all share the costs.

Derek Cascio, an industrial designer with Phillips’ LED lighting unit Color Kinetics in Burlington, Massachusetts, and Sam Aquillano, an industrial designer with Bose in Framingham, Massachusetts, are co-founders of Design Museum Boston. “People believe industrial designers are sort of like corporate hairdressers,” Cascio says. “We’re creating the museum to help educate the public about all design: industrial, interior, architectural.” Acquillano adds, “New England is second only to the Bay Area in numbers of designers. In Massachusetts alone there are 44,500 designers: architects, interior designers, landscape, video games, fashion. Almost every aspect of our lives is impacted by a designer.” The museum will actually be a series of roving installations, the first of which is planned for Boston City Hall later this year.

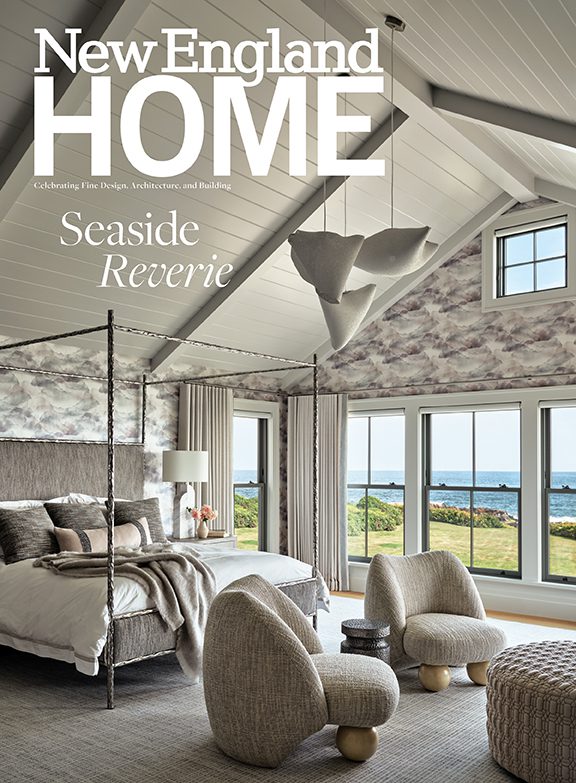

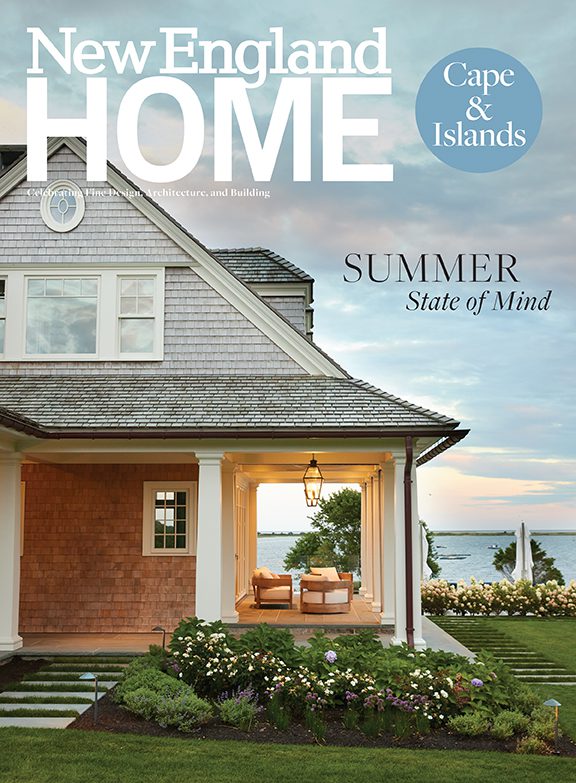

Sometimes designers have their own long-held beliefs, like the one that’s so convinced that “everything across the pond is far more elegant!” Cheryl Hackett, author of the recent book Newport Shingle Style, says, “After the 1876 Expo celebrating the U.S. Centennial, architects such as McKim, Mead & White and Peabody and Stearns said, ‘What are we doing copying European architecture?’ They became fascinated by the early settlers and went on tours sketching colonial homes. The result was what we call Shingle Style.” She cites Newport’s Isaac Bell House—a McKim, Mead & White work—where open floor plans take advantage of the sea breezes and ocean views. “It’s so playful, so inventive,” she says. And just as beautiful as anything European. Hackett is now working for The Newport Collaborative, whose “Out to Sea” residence at Carnegie Abbey (built by Woodmeister Master Builders) is deservedly on the book’s front cover.

There’s a common belief that you need to hire a local architect, one steeped in the local vernacular and one who knows all the other players—contractors and subs—in the area. However, Morehouse MacDonald and Associates, of Lexington, Massachusetts, run contrary to that belief. Says John MacDonald, “We’re doing jobs all over: Scottsdale, Arizona ( a ‘tweener’ sort of Spanish colonial adobe meets Yankee), an Italianate manor house in Naples, a barn in Vermont, a Victorian cottage on a lake in New Jersey.” In many cases, these are repeat clients who are using the firm for their retirement or vacation homes. “The fact that we’re willing to get on an airplane and go to them makes our clients happy. They trust the relationship they’ve built with us,” MacDonald says. “It’s nice for us, too. Boston’s pretty competitive; it seems more easygoing in the West and South.” As for choosing the right builder, MacDonald calls the AIA for the names of top builders in the area, then interviews them, checks their references and so on. “It works out pretty well,” he says.

Forget about the notion that “classic New England” is all about a cottage look in serene neutrals. Tracy Davis of Urban Dwellings in Bath, Maine (where you can hear sturgeon splashing in the Kennebec outside her office window), says her clients are telling her, “We’re done with cottage style. We want modern and give me color. Don’t give me anything white!” So, for example, she says, “We just did a mudroom with built-in boxed seating in a rich wenge-like finish inspired by Japanese Tansu benches. The cushions are in spiced pumpkin as is the cabinetry along the wall. We graded the hues of pumpkin cabinetry, so as you move from left to right they darken. The wallpaper is in a large paisley in orange and chocolate.”

Designer Linda Stimson of Inner Visions Interiors in Lexington, Massachusetts, is seeing more requests for color, too, especially from younger clients. She writes from her Blackberry: “I am seeing people under thirty painting entire rooms in fuchsia with white and indigo accents. Also deep rust, or red rooms for warmth and security.”

A particularly stubborn belief about people who work in design is that they’re either right brained (slightly weird, creative) or left-brained (analytical, logical) but not both. Architect Stephanie T. Horowitz of ZeroEnergy Design, Boston, and one of New England Home’s 5 Under 40 award winners for 2010, begs to differ. “Our work takes a much more holistic approach,” she says. “The design is both beautiful and informed by our calculated approach to building performance; it’s the complete package. My firm is of the belief that the beauty and brains of our design are inextricably linked.”

Now that’s a belief we can hold onto.

Share

![NEH-Logo_Black[1] NEH-Logo_Black[1]](https://b2915716.smushcdn.com/2915716/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/NEH-Logo_Black1-300x162.jpg?lossy=1&strip=1&webp=1)